Hunkering Down at the Alte Nationalgalerie

I was looking forward to viewing the Karl Friedrich Schinkel architectural drawings tucked away on the third floor of Berlin’s Alte Nationalgalerie. Schinkel designed many of Berlin’s iconic neoclassical buildings, including the Altes Museum and the Konzerthaus. However, the third floor was closed due to the installation of an upcoming exhibit. As a consolation, I switched gears and decided to “curate” my own show that might be called “Hunks on the Second and First Floors of the Altes Museum.”

Starting with The Archers (above), this Pre-Raphaelite-style painting updates the classical theme of a group of archers into, for its time, a contemporary picture. Although the figures are idyllic, the body language is naturalistic - the one on the left bending down, bracing on one knee, the one on the right arched back, attentively looking skyward, and in the center the figure is tensed and waiting for the critical moment to release the tension of the bow. The drab, flat landscape is contrasted by an active sky. The men are essentially separate from each other, but connected by their common mission and their nakedness.

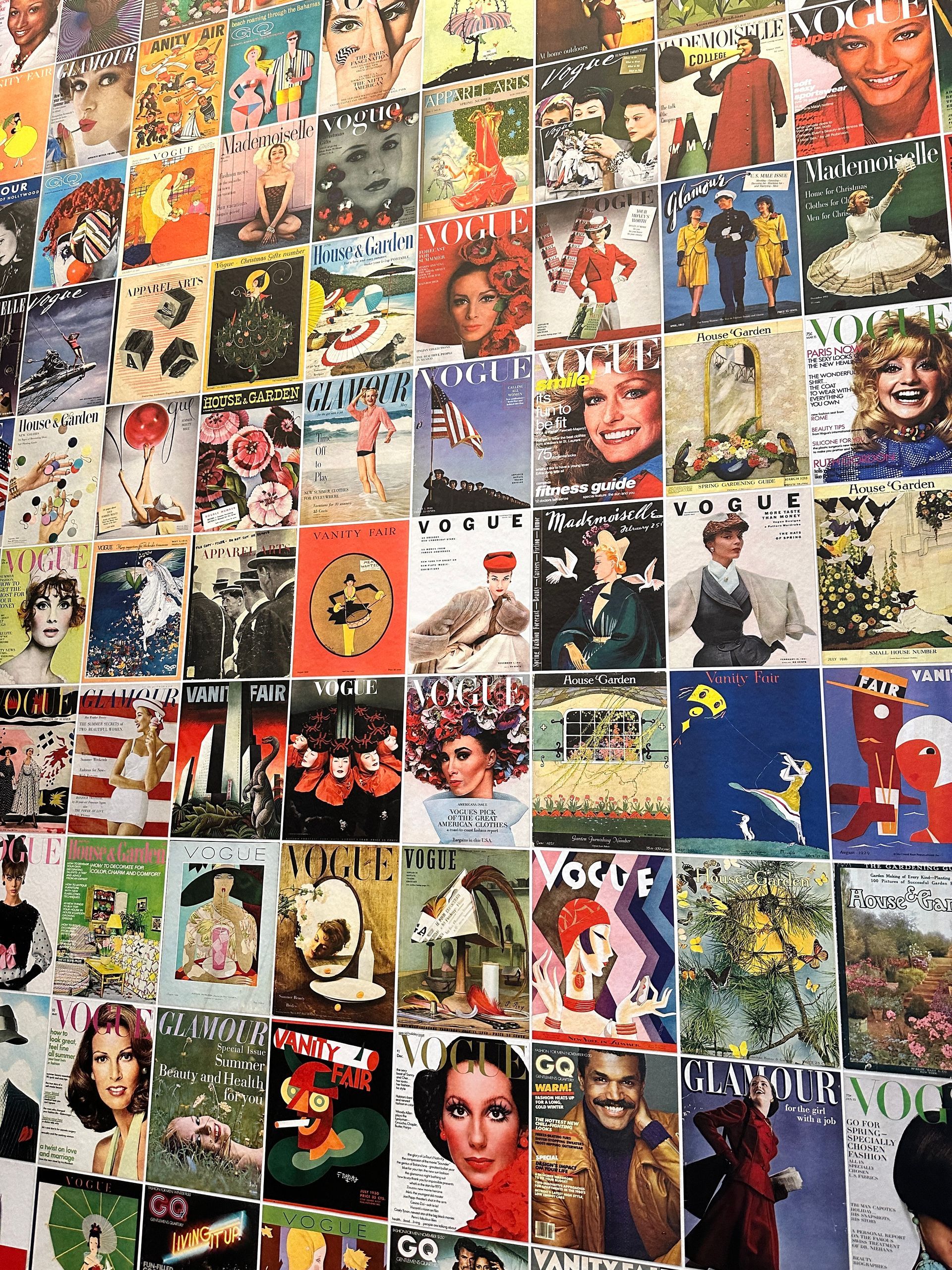

Pre-Raphaelite and Symbolist painter Arnold Böcklin, painted this portrait of his friend Karl Wallenreiter. The face is handsomely framed in front of a neutral gray pillar, bracketed by glimpses of turquoise water or sky and neutral green-gray foliage. The quiet drama of the painting moves between the warmth of the face and the hand grasping a music scroll. So much to take in and enjoy in this portrait - not only the technical stuff, but ultimately the presence of an accomplished person.

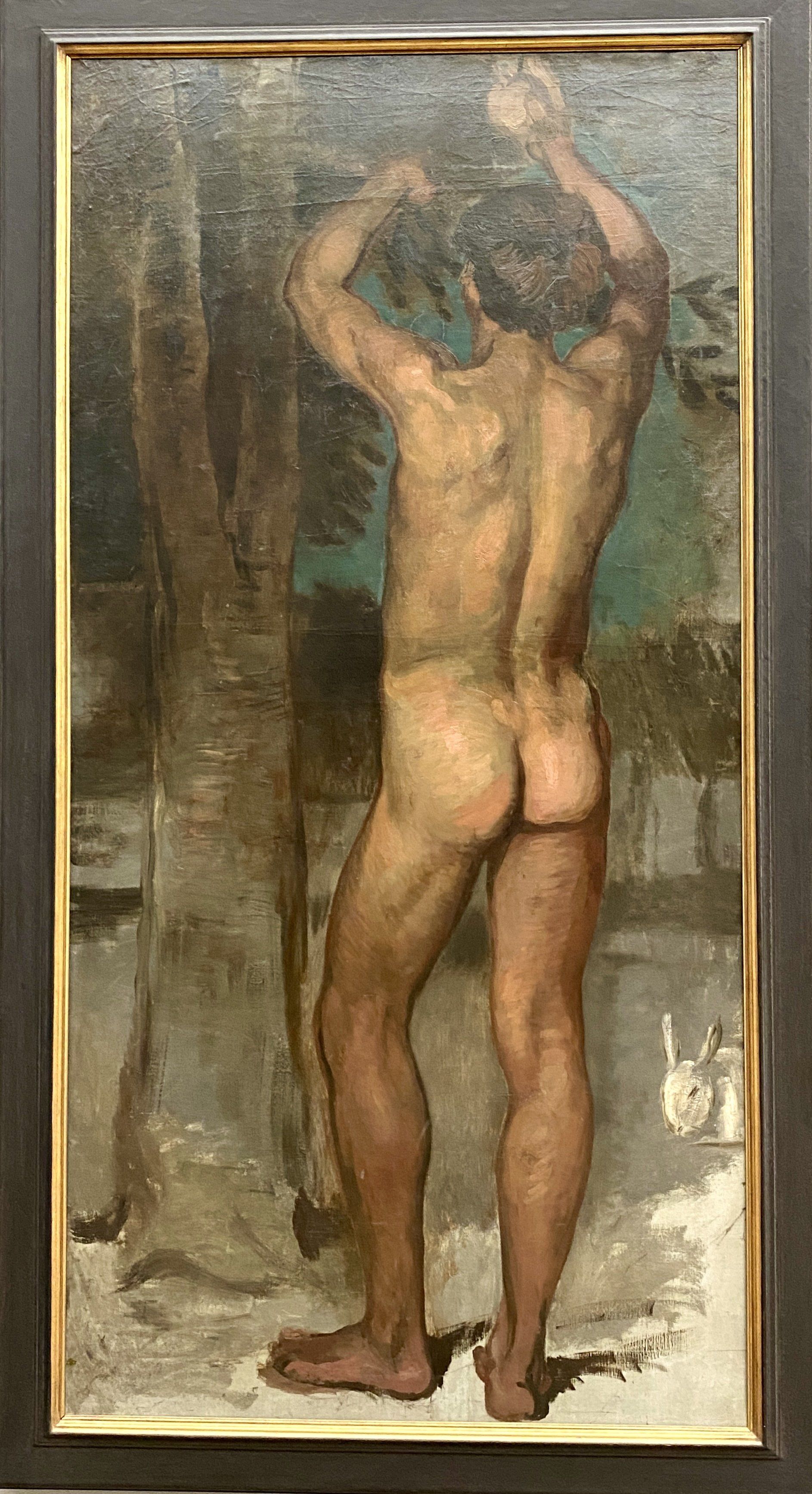

“Orange Picker” by Hans von Marées was associated with the German Romantics, however his approach to the figure in this painting is a stone’s throw away from Cézanne.

Apologies for the glare at the top of the picture.

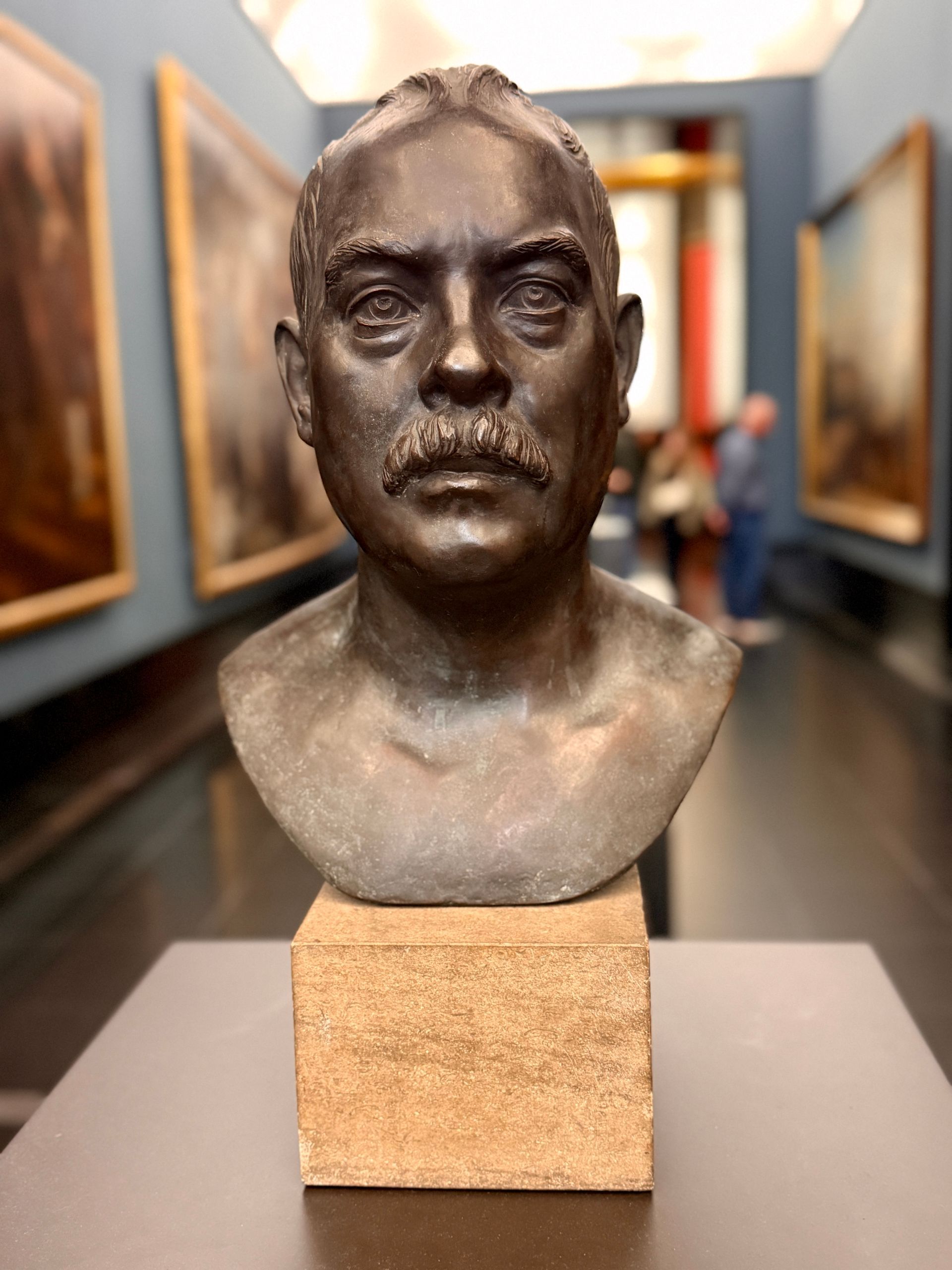

Rodin had a Belgian soldier pose for this statue. When the sculpture was first exhibited, Rodin was falsely accused of making the statue from a direct cast of the model. The charge ended up being good publicity for Rodin because it ramped up public interest in the statue. The figure is “open,” meaning aside from the solidity of the torso and trunk, there is ample air space between the arms and the body and between the legs, giving the statue lightness and a feeling of movement. Rodin treads an interesting line between romanticism and naturalism. When looking at the statue, it’s easy to believe that this portrays a real person, yet it expresses “the many” as well.

Casts of the statue are on view at numerous museums, including the Honolulu Museum of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, and the Legion of Honor in San Francisco.