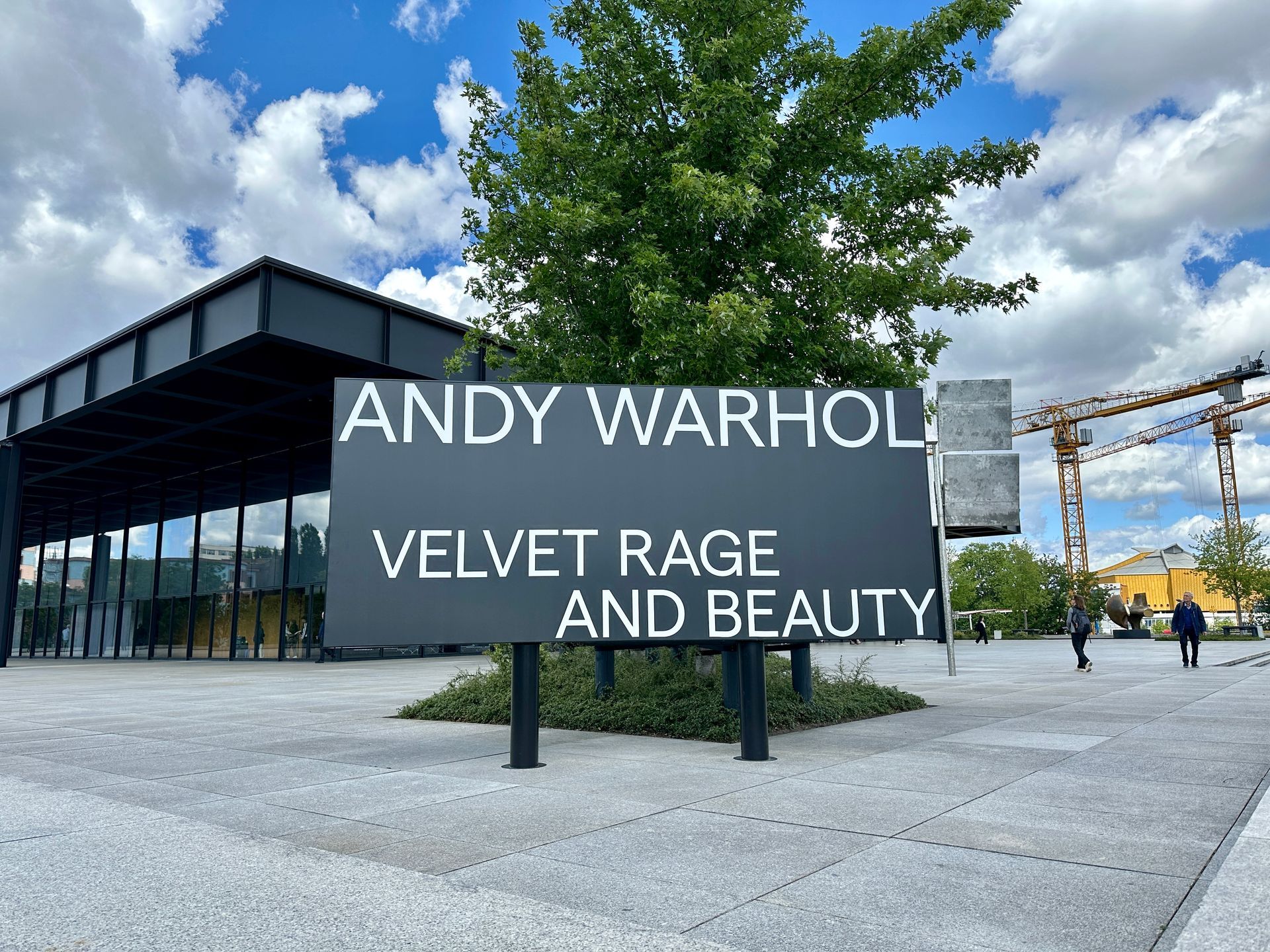

Sex, Beauty and Gay History - Warhol Style

“Velvet Rage and Beauty,” the current exhibit of Andy Warhol’s homoerotic art, and the accompanying historical context reveal who Andy was: an extremely creative, hardworking person who knew from the very beginning of his career what he was doing - but due to his times, was obliged to “back shelf” his sexually explicit work. Even though some of this work was exhibited at small venues in Europe and in the United States during his lifetime, Warhol’s New York dealer Leo Castelli, would not show the work, presumably because he either thought it was not salable or he felt he needed to protect his world-class gallery’s reputation.

The Neue Nationalgalerie exhibit, which includes more than 300 paintings, drawings, photographs, Polaroids, films and collages is an unexpurgated representation of Warhol’s sexuality.

From dingy bathroom stalls to the ruins of Pompeii, erotic subject matter has always had a niche in human image-making. This exhibit represents what erotica looks like when aesthetics are at a high level and money is no object. The work in the exhibit ranges from elegant and ingenious to flat and pornographic - the whole range is included in this show.

It’s easy to forget what it was like to be gay before 1970, or for younger people, pretty much impossible to imagine. Repression was solid in every corner of American society - enforced by the law, underscored by families, and condoned by religious organizations. Within this context, Warhol’s erotic work is … erotic of course (maybe even juvenile at times), but also very political. People have a basic right to free expression, and Warhol claimed that freedom - although that freedom would not be completely realized until now, as Neue Nationalgalerie brings this work into public view. The museum posted disclaimers and warnings at the entrances to give the public a heads-up about the graphic sexual images in the exhibit. The most explicit pieces happened to not be in my "favorites" category, so the images I am showing in this blog posting are among the most tame.

Here are some of my favorite pieces in the show:

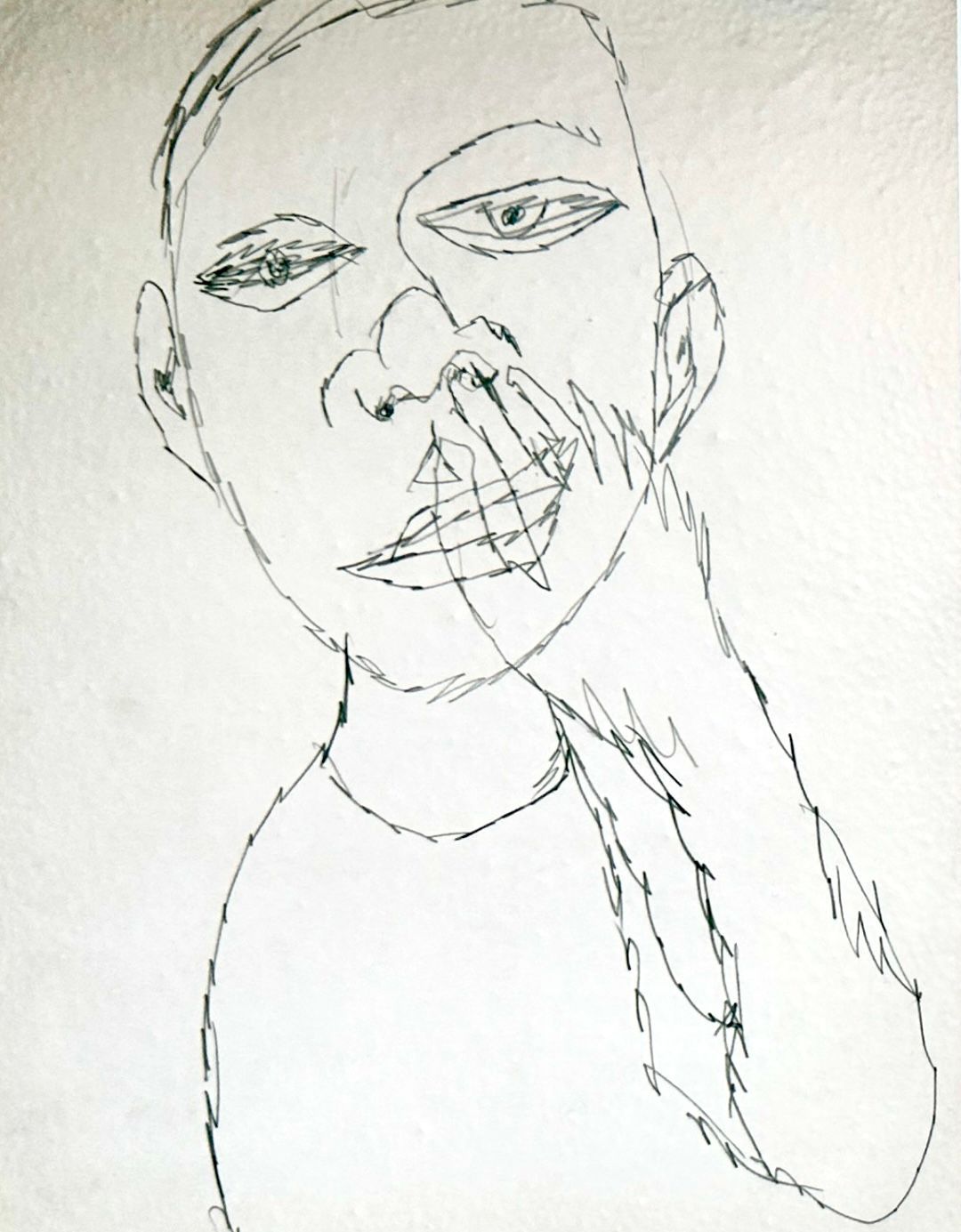

Demonstrating his wiseacre tendencies in high school, Warhol did this drawing (below), which he titled “The Lord Gave Me My Face, but I Can Pick My Own Nose.” He entered the drawing in a Associated Artists of Pittsburgh juried show, only to be rejected. He retitled the piece, “Don’t Pick on Me,” for a student exhibition later that year.

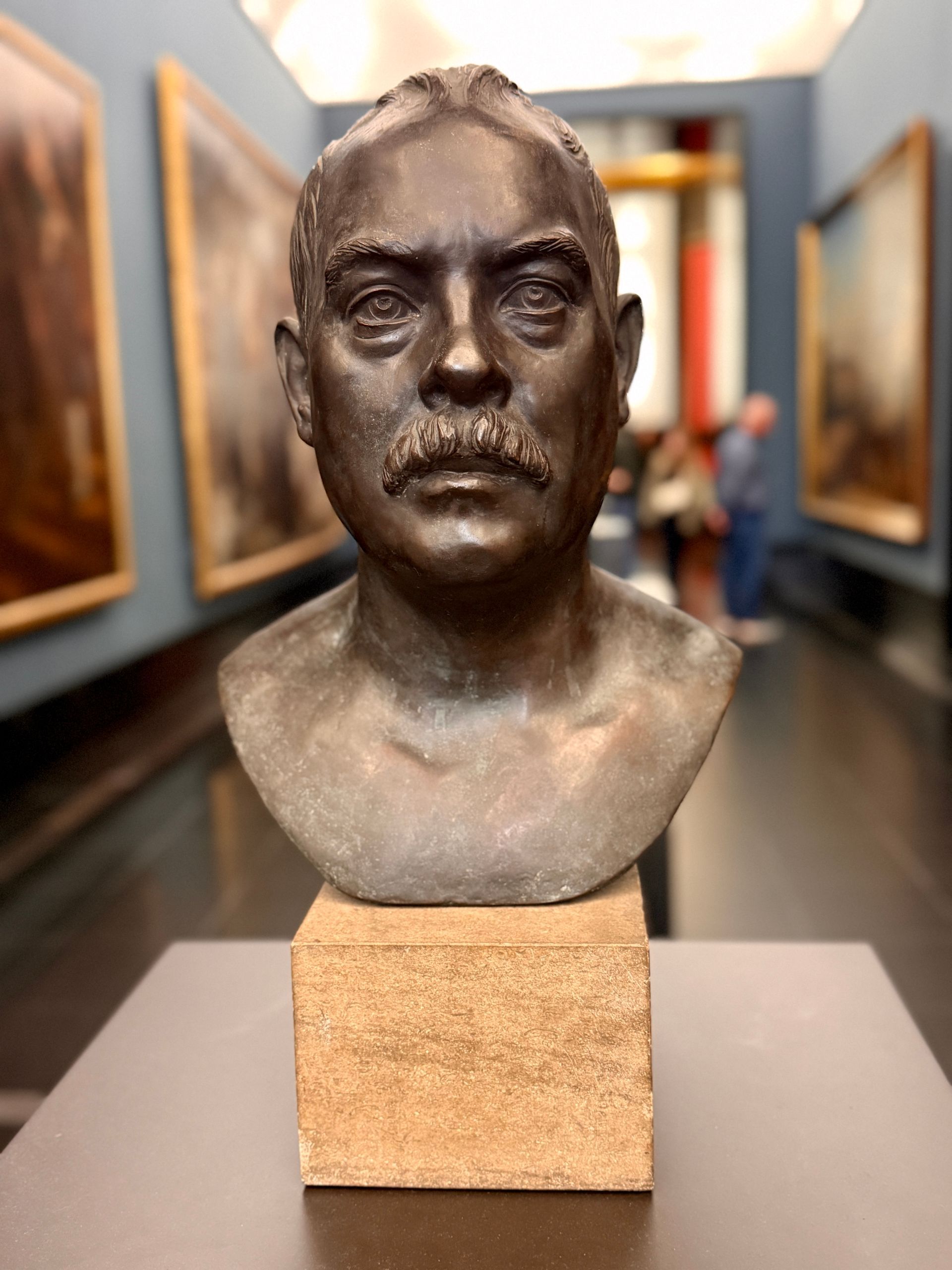

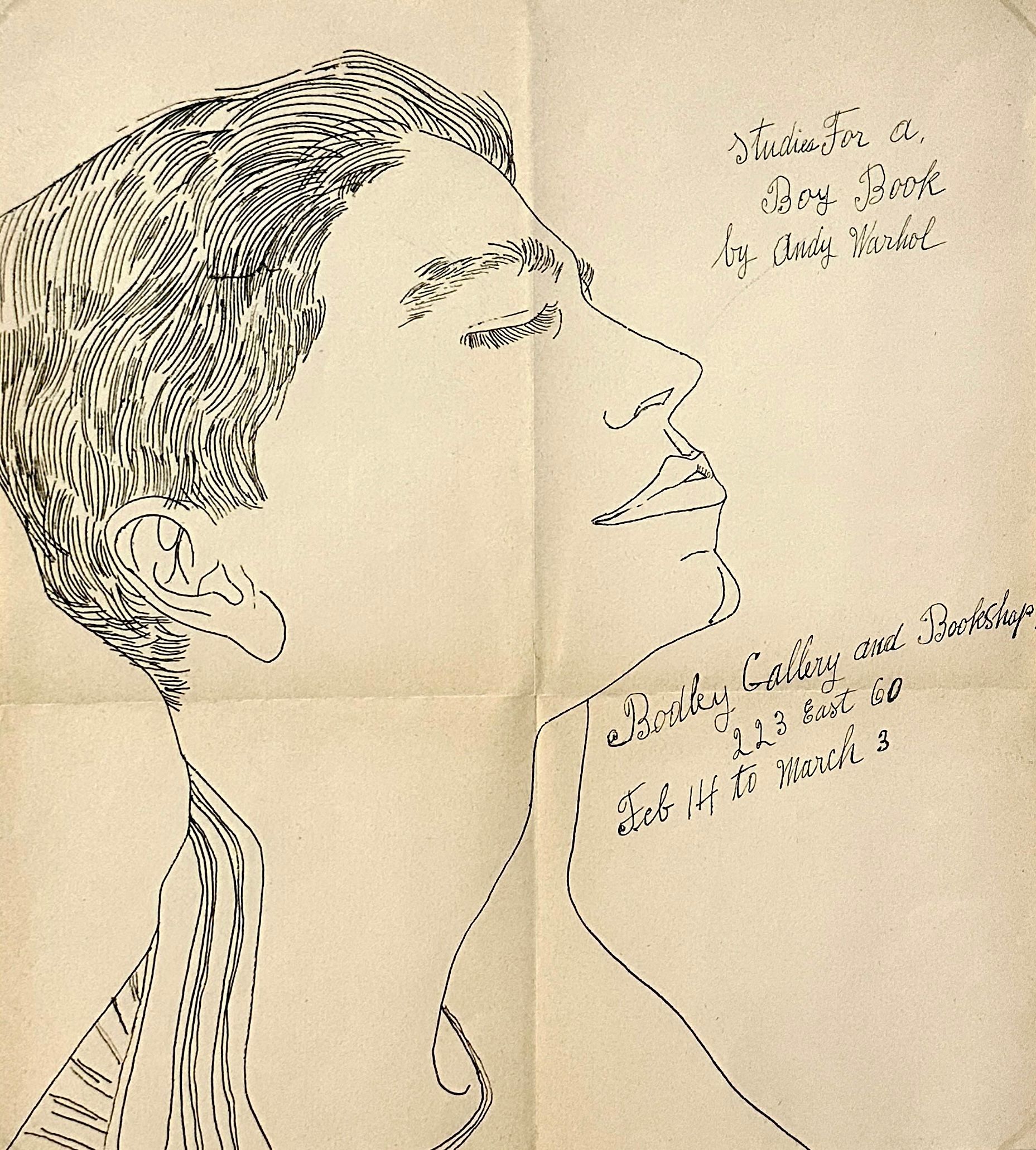

The lithograph design below for Bodley Gallery in New York City predates his Campbell’s Soup Cans by 6 years. The design shows Warhol’s sensitive line style that he developed as a commercial artist, while giving us a preview of the attitude captured in his later silkscreen portraits.

Already in 1964 Warhol had introduced a revolutionary approach to portraiture: a moving picture that hardly moves. What if you could see the Mona Lisa as a living, breathing, and occasionally blinking young woman? This model is very much like a modern Mona Lisa, who stares at the viewer with almost no expression. I’m surprised that this take on portraiture hasn’t been more exploited.

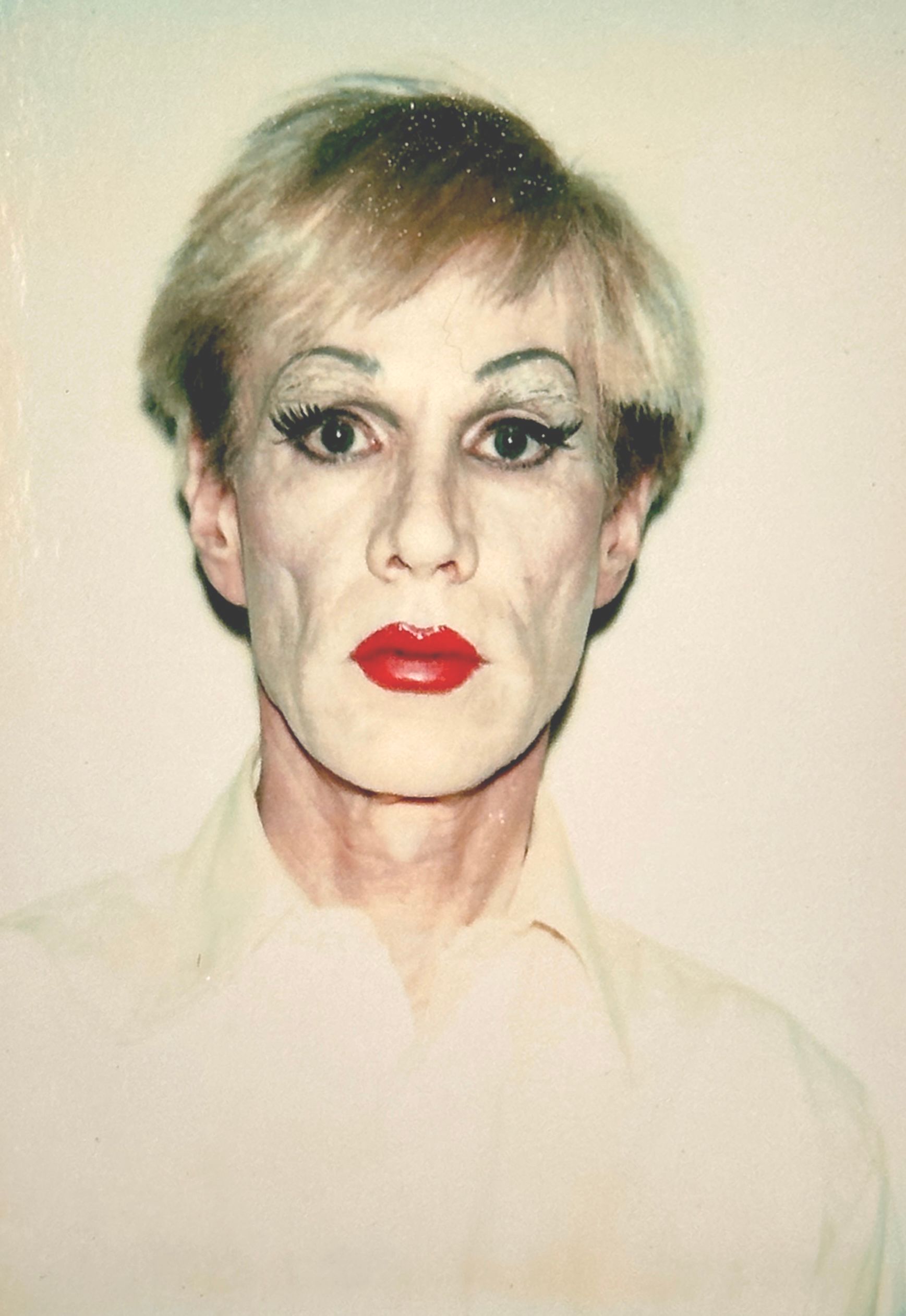

This self-portrait in drag was taken eight years after the assassination attempt on Warhol and seven years before his untimely death after gallbladder surgery. The Polaroid brings up the question of “Who is this person, really?” However we physically present ourselves on a day-by-day basis, the authentic self exists behind the facade. Depending on the circumstances, we selectively reveal parts of ourselves. But some of the facade actually becomes who we are to others and even to ourselves.

This image of transgender actress Wilhelmina Ross, was part of a series based on over 500 Polaroids taken of 19 models, some of which were used as source material for over 250 silkscreen paintings. Wilhelmina was one of the most featured personalities. The painting celebrates her talent and fortitude in the face of the prejudice and poverty that ended up claiming her life in 1991.

This “out-of-register” silkscreen portrait, in the classic Warhol style, captures Marsha P. Johnson more accurately than any literal interpretation could. Johnson fought on the front lines of the 1969 Stonewall uprising, and her exuberance, warmth, and empathy are expressed in this painting.

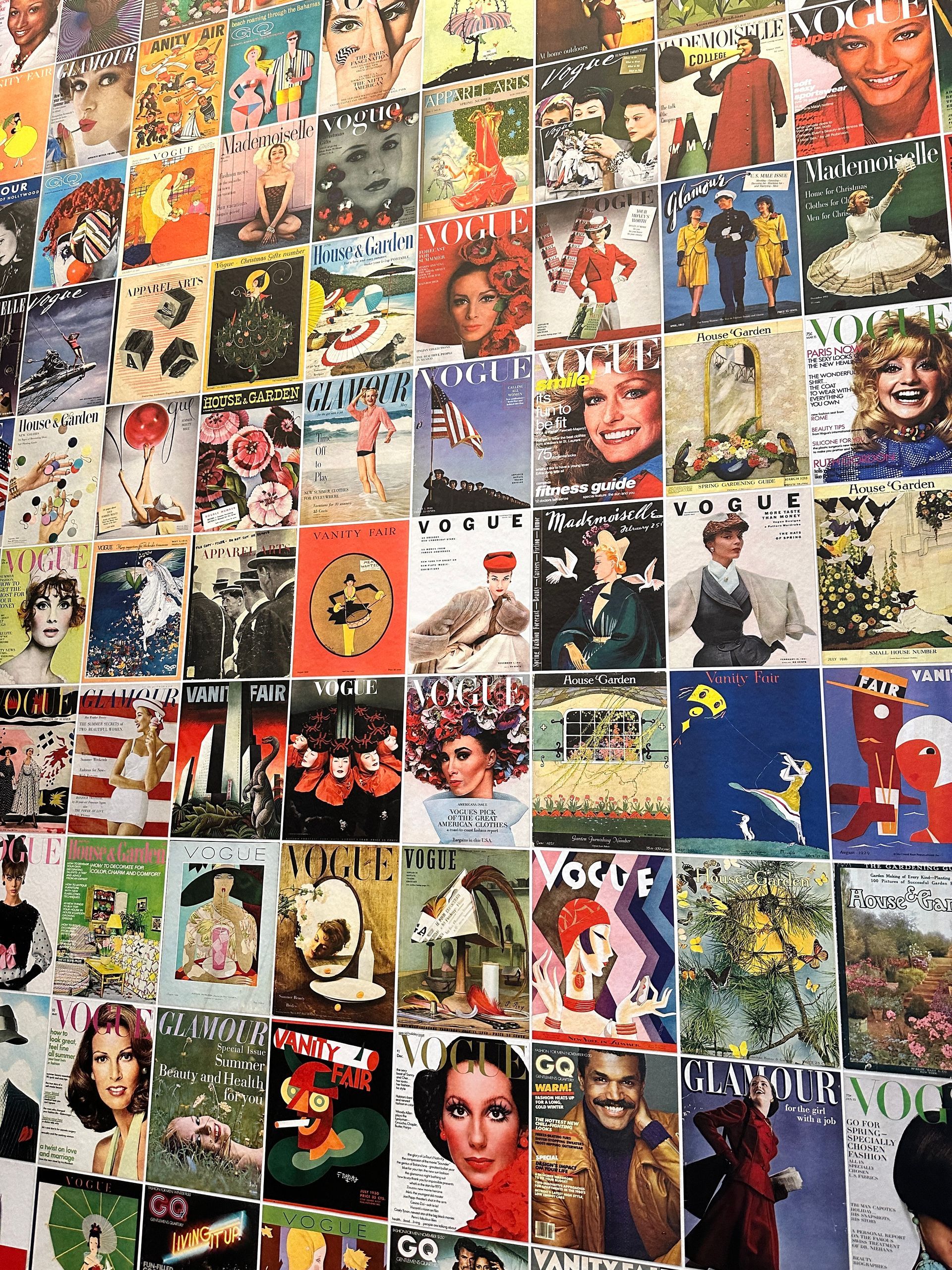

By fetishizing the male figure, Warhol transforms how we view the male body in art and updates the concept of what is “classical” in painting and sculpture.