Bill Viola retrospective addresses themes that never go away

Before I get into the exhibit “I Do Not Know What It Is I Am Like – The Art of Bill Viola,” I have to say the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia is really a unique, beautiful place. The building is straightforwardly elegant, composed of straight lines, which are echoed in a reflecting pond. At one end of the pond, a polished steel Ellsworth Kelly sculpture vaults skyward. At least when I was there, every staff person, from the greeter at the door, to the museum guards, to the people in the gift shop was genuinely helpful. At one point, I was scribbling notes with a ballpoint pen, and a guard came over to me and told me ballpoints weren’t allowed in the museum, which is not unusual, but then she went the second mile and handed me a newly sharpened #2 pencil with a clean eraser on it. Wow.

The collection, which is mostly Impressionist and early 20th century European and American painting, is stacked up the walls, salon style, in the same configuration conceived by Albert Barnes, who founded the original museum in Merion, Pennsylvania.

This small museum alone justifies a trip to Philadephia!

On to Bill Viola!

How many video installations have we all seen that occupy a darkened museum room, furnished with a bench at the back, the only light source being grainy images flickering on CRT TV screen? You enter the room and give it some time, hoping for something to happen. Then you feel a twinge of guilt, because after all, the piece actually made it into a museum, right? I often felt there was a double standard regarding video art, which sometimes didn’t seem to pass the same test as the other modern masterpieces in the building. Technology has leaped forward since video art started claiming museum real estate, and the automatic “ooh’s” and “aah’s” for video work now seem to be harder to earn.

Viola is doing something not currently in fashion, to say the least: He addresses theology and “faith” in his pieces. Sometimes his topics are directly from Judeo-Christian scripture, however his theological ideas can be framed through a humanist lens as well. For example in the piece, “Ablution,” he makes reference to Christian water rituals – baptism and footwashing. But even if the viewer has had no religious education, he or she can get the symbolism of water as an agent of cleansing, renewal, and new beginnings.

I became a Viola fan years ago, simply responding to the visual poetry of his work.

Bill Viola brings vision and technical virtuosity together. His work is “stilling.” Viola puts the viewer on the offense, meaning the viewer is not being asked to passively watch, but to engage.

“I Do Not Know” only includes seven pieces, but with Bill Viola, more is not necessarily more.

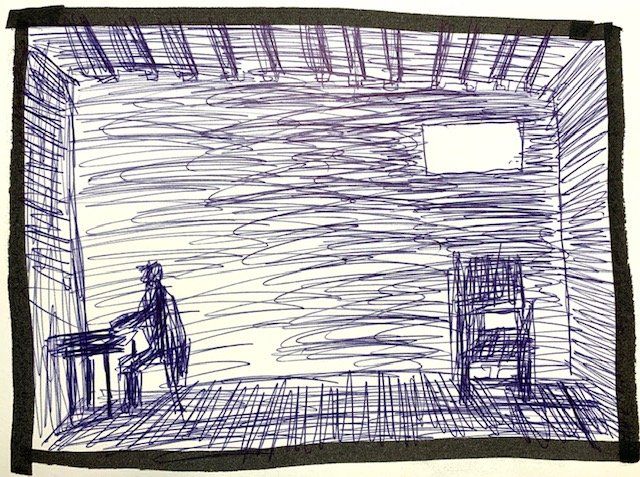

Photography is not allowed in the exhibit, so here are some of the sketches I did of the show.

The exhibit continues through September 15, 2019.

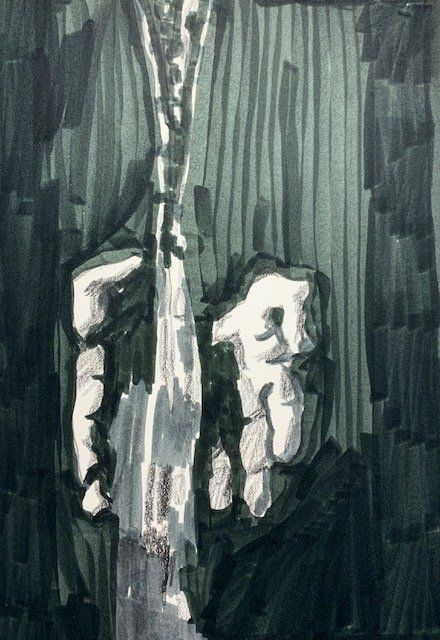

Ablution, 2005, 7 min., 2 video panels

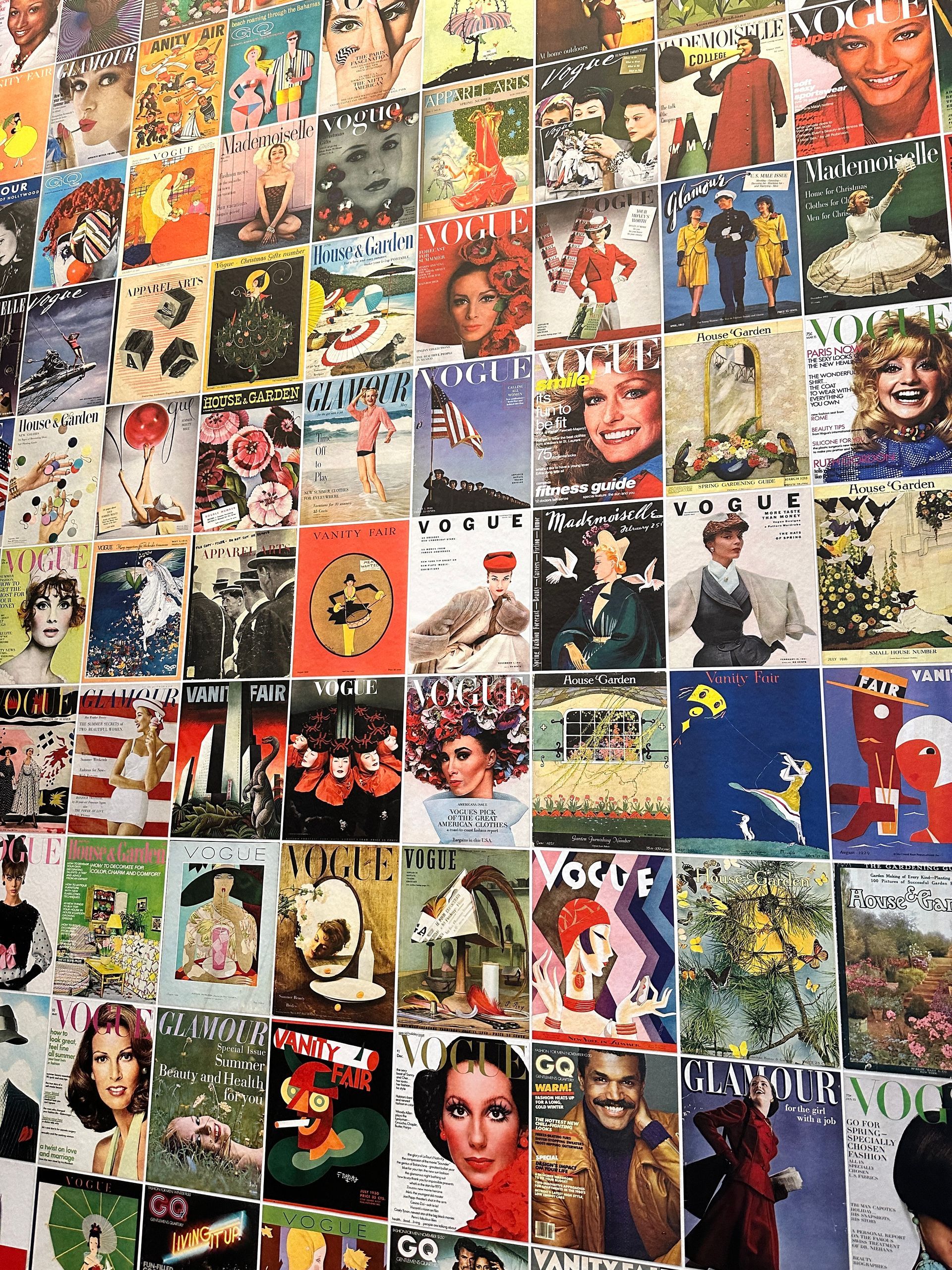

Ablution is a dyptich (two vertical screens) reminiscent of an altarpiece. A stream of water flows the length of each screen over over two pairs of hands, a woman on the left and a man on the right. Their unclothed torsos are in soft focus, behind the hands. As Warhol discovered, repetition has power – even if it’s just two.

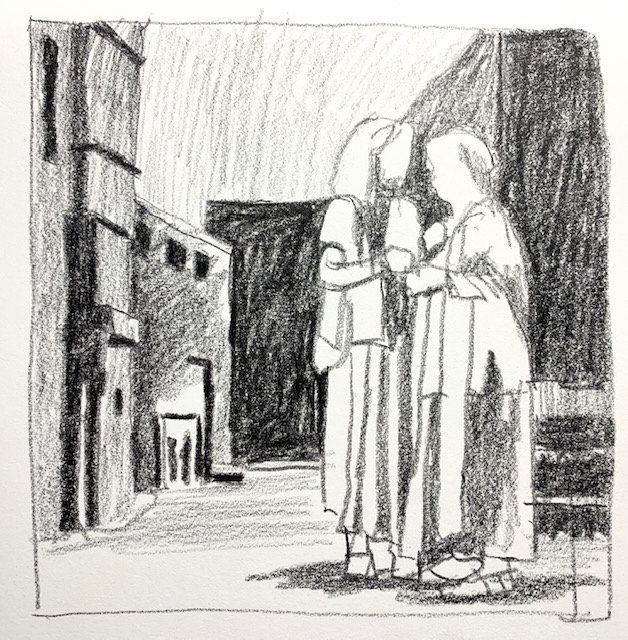

The Greeting, 1995, 10 min., 1 video projection with sound

This video depicts two and sometimes 3 women in a happenstance meeting on a city street, seemingly catching up on news, sometimes displaying empathy, sometimes distanced and dispassionate. The background is like a stage set, and establishes deep perspective. The mood and colors have the feel of a de Chirico painting. The women are wearing clothes that would be appropriate for a shopping trip or museum-going, but not for work. The flowing dresses have a classical Greek or Roman look and move gently in the breeze that comes from an off-camera fan. Time is passing, but strangely also standing still. Really interesting piece.

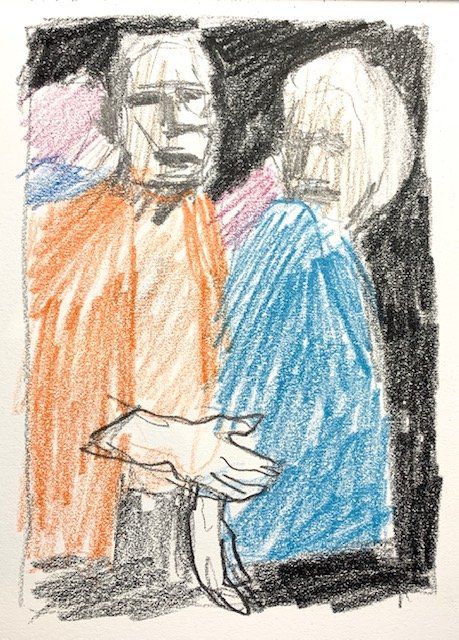

Observance, 2002, 10 min., 1 video panel

This piece shows a group of people who are presumably attending a viewing at a funeral. One by one and in pairs, people approach the deceased, who is out of the camera frame, and silently reveal a range of restrained emotions. Like the people pictured in the funeral “reception” line, we the viewers bring our own memories of confronting death.

Catherine’s Room, 2001, 18 min., 5 video panels

This Vermeer-like room is shown on five video panels. Each panel portrays a different time of day and a different time of year. The first panel is morning, the second is the workday, the third is a mid-day assessment of the day’s activities, the fourth is a time of evening prayer, and the fifth is night. The room is a monastically simple setting, and generic enough to represent any living space. The lighting changes panel-to-panel, corresponding to the time of day, and the furniture changes in each panel, which indicates that this is not one 24-hour sequence. This piece is about the rhythm of life, self-awareness, responsibility and completion.

Ascension, 2000, 10 min., video projection with sound

The camera is positioned 25 feet under the surface of the water. The only disturbance in the occasional stream of bubbles coming from down below. Suddenly a body crashes through the surface and plummets down. The person appears lifeless, and with arms stretched out in cross form, slowly rises to the surface. The Biblical references are obvious. In addition, the viewer is captivated by the beauty and technical inventiveness of the scene, and confronted by a limited view of a death that may be due to foul play. The body keeps rising, but before breaking the surface, starts sinking again, and eventually sinks below the camera frame.

He Weeps for You, 1976, copper pipe, live camera with macro lens, amplified drum, video projection

This is a live action video, which shows a macro view of water

dripping from a copper pipe, and then the drip strikes a shallow drum below. You're seeing the live hardware and action and the simultaneously projection of that action on the screen, where you can also see yourself magnified within the water drop. The piece compares a

“real thing” with a depiction

of a real thing. The hardware is interesting by itself, but then the

live image provides a "translation" of a 3-D experience into an enlarged 2-D image. It’s

like the following question: How do these three experiences differ? 1) standing

in front of and looking at Yosemite Falls, as compared to 2) looking at a photograph of

Yosemite Falls, as compared to 3) looking at a painting of the photograph. Each one of

those experiences is different, but all three have the same content.